STEVE CLORFEINE: WRITER, DIRECTOR, TEACHER, PERFORMER:

INTERVIEW WITH TERRY STOLLER, DEC. 2019

April 10, 2020

Terry Stoller spoke with Steve Clorfeine about his interest in sports and dance as a youth, his association with the Gurdjieff Foundation, his experiences at the Naropa Summer Institute, his performance work with Barbara Dilley and Meredith Monk, and the multiple tracks of his life as a performance artist, teacher, and writer.

Terry Stoller: You grew up in New York City, and you’ve said your parents were culturally involved. They did folk dancing, and you accompanied them to local folk dance groups. But you also said you didn’t think of that as something you would do with your life. What were you thinking you would do with your life?

Steve Clorfeine: I remember that by the time I was 11 or 12, when people would ask me that, I would say, I want to be a beach bum or I would I say I want to be a baseball player. I was an avid baseball fan. I loved playing ball, any kind of ball – baseball, basketball and all the variations of ball that we played in those days, punchball and slapball. At my grandmother’s place, we would play stoopball. Those were my two stock answers – beach bum and baseball.

It sounds as though you were very athletic as a boy, dancing and playing ball. Interestingly, later you get involved in physical performance.

I don’t think I ever made that connection to a career or a vocation. My sister was the one who could have been a professional dancer. There was some influence there. She was taking classes with Donald McKayle at the New Dance Group. I would watch her choreograph pieces in the living room. I would put the record on for her and sometimes dance with her.

My father was a really good social dancer. By the time I was 12, I was social dancing a lot. We had a cohort of kids who would have ‘socials’ at different apartments on a Friday night, and we would put on 45s and dance. I remember going on a dance TV show called The Clay Cole Show. That carried on into junior high school. In high school, everything stopped. I went to Stuyvesant High School. It was an all boys school at that time and very competitive. I was doing what I thought I was supposed to be doing, studying as much as I could, getting the best grades I could.

When you were at Stuyvesant, did you have an idea of what you were studying toward?

No clue. I knew what I liked. I liked language and literature and history. In those days, it was common and more than acceptable to go to a liberal arts college and get a liberal arts degree.

Were you writing then?

I was always writing, but mainly for writing classes, papers, essays. I remember my last year and a half of college, I wrote what I thought were more visionary papers. I was doing seminars at the University of Rochester. It was a very intellectual college. My major was intellectual history. There was something that really clicked for me in that. I’m not sure I’ve ever put it to great use. Except in the various ways I’ve been teaching in my life.

During my junior year, I studied abroad in Paris. And at the end of that time in Europe, I did not want to come back. But I did and I was miserable. Then I was pretty much pressured into going to graduate school to avoid the draft. I had to think about what I would do in a graduate school. What I could truthfully say for myself was that I love to travel and I love to interact with people. If I had to say something, I’d say, I’d like to work for the United Nations, even hough I had no idea what that would entail.

Now they call that International Relations.

That’s the school I was in at Columbia, the School of International Affairs. When you entered you had to choose a regional institute of specialization, and I chose the Eastern European Institute During my traveling time in Europe I had fallen in love with Yugoslavia. We drove along the coast It was my first taste of the way people lived in villages, a fishing culture. I was completely charmed by it. When I got to the School of International Affairs, I was the only one in the class who had a beard, and I knew I was out of place. I was struggling with depression, not knowing what I was doing, and not wanting to be in graduate school. I was living by myself in a studio apartment on the Upper West Side and going to Columbia, and it was boring as hell. The teachers—law professors and international relations people—were reading from the books they had written. In one class the professor told me that because I had been involved in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC], I would never be allowed to work for the United States in the United Nations. That sealed the deal, and I realized this was not for me.

Despite the risk, I would have dropped out had the 1968 student rebellion not occurred at Columbia. I got very involved in that, and I wasn’t depressed anymore. I had a girlfriend. I was arrested. I got very active in the community. It was an exciting time. There were three of us from the School of International Affairs who were arrested; we had joined a sit-in in Fayerweather Hall. Later the dean of the school interviewed us about coming back to finish our program, and I got a full scholarship. I just basically made up the courses I wanted to do. One of them was Balkan folk dance because there was a master teacher at Barnard, Martin Koenig who gave a real training. I think that was my entrée to formally dancing.

When did you begin teaching Balkan dance?

That came in 1973 when I was teaching at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

At what point did you get involved with the Gurdjieff Foundation?

That was in New York City, but it actually started in Rochester. There was a large Gurdjieff group there. I had a distant cousin who was married to one of the leaders of that group. I would hang out with them but I didn’t know it was anything spiritual. I just thought my cousin’s husband was a really cool guy. He gave me different tasks to do, which were Gurdjieffian tasks, but I didn’t know that. They had to do with paying careful attention to things, a kind of active mindfulness. Slowing down was also part of it. They were very slowed down. They were careful about what they did and how they did it, and curious about what the roots and sources of things were. At that time, I had a near death experience in Rochester and I was quite vulnerable. I contracted spinal meningitis. I got to the emergency room just in the nick of time. That was a wakeup call for me.

Had you studied Gurdjieff in school?

In those days, one wouldn’t have read about Gurdjieff. It was pretty secretive. My parents didn’t know. My colleagues didn’t know. That’s the way it was presented to me. I had this connection from Rochester, but when I asked if I could be part of the Foundation in New York City, I was told to meet a woman who would be wearing a certain color coat in the lobby of a certain hotel. And that’s what I did.

What were you finding in that group that appealed to you?

I think I was aware of something very unsatisfying in my being—and nothing I was doing or would be doing was going to change that. It had to come from somewhere else.

From 1971 to ’74, you were on the faculty and later the director of the Experimental Studies Department at New Paltz. That must have been a really good job, but you left it.

That was one of the only full-time jobs I’ve had in my life. I think I already had an inkling that I was not going to be happy in the academic world, even given the freedom I had and that freedom was coming to an end. The State University was coming down on that program. I knew it would soon be over.

How did you hear about the Naropa Summer Institute?

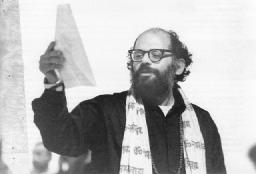

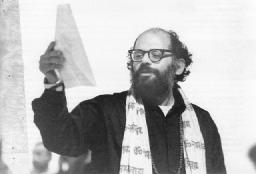

The last class I taught at New Paltz was called ‘Autobiography of a Search.’ I was kind of outing myself as a Gurdjieff person. We were reading Western autobiographies of spiritual people and during that semester the news about the first summer program at Naropa was circulating. In the middle of the summer I called someone I knew at Naropa who was doing the program, and said I wanted to come out there. I was there for the last two weeks of the program and that’s when I fell into everything that was to follow. That was the beginning of my exposure to Buddhism, to Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, to Allen Ginsberg and the Beat poets, and simultaneously my introduction to performance because I worked with dancer Barbara Dilley that summer. For two weeks, I worked with her, and at the end of it I was so moved by what we were doing.

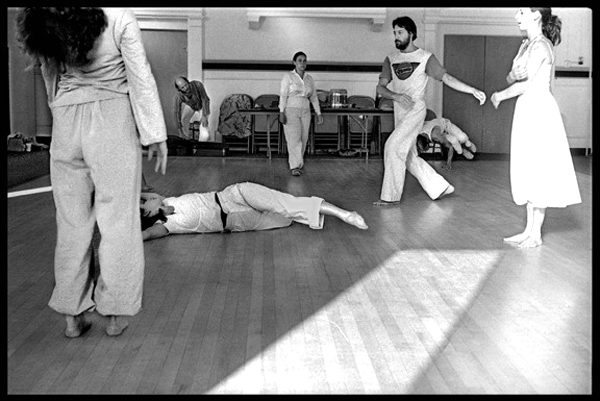

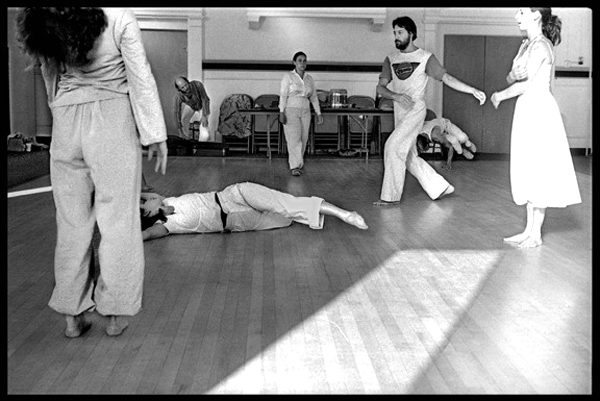

Steve Clorfeine (second from right) rehearsing with Barbara Dilley’s company, Naropa, 1976.

Would you describe what that was?

Steve Clorfeine (second from right) rehearsing with Barbara Dilley’s company, Naropa, 1976.

Would you describe what that was?

The movement was basically pedestrian movement . We improvised and there was a theatrical aspect to it. It wasn’t about being a dancer but about engaging in relationships through time and space. It was something that Barbara was exploring for herself, having come out of the Merce Cunningham company and out of the improvisational troupe the Grand Union. I privately mentored myself by watching that group perform. At the end of those two weeks in the summer, I said to Barbara, I’m moving back to New York City. I’d like to take class with you. And I remember her saying, I want you to. But first I hung around out West, went to Oregon and New Mexico. When I was in New Mexico, I got a letter from Barbara saying, I have a performance at the Kitchen in November. I want you to be in it. I came back to the city at that point and did that performance—which was the first performance at the Kitchen when it was in SoHo—and then I continued to work with Barbara. It was all improvisational movement. There were structures, but there was no set movement.

How comfortable were you doing that?

It was edgy for me because I was such a newcomer to that world. This was SoHo in its heyday, 1974, 1975. I was a newcomer to the avant-garde, and I was surrounded by dedicated experimental artists.

Weren’t you involved in experimental studies at New Paltz?

I was. I created the ethnic dance and music program. That’s when I invited Brenda Bufalino to teach, as well as a Native American dancer, an East Indian dancer. I was teaching Balkan dance, and I was taking tap and jazz with Brenda.

How did you meet Meredith Monk?

The second summer of Naropa, I went back as Barbara’s assistant. We rented a big house together, and everybody came through that house as guests—and Meredith came. I remember she was sitting on the front step with her suitcase when I came back from class. We immediately started talking about Gurdjieff. That was the ground of our friendship. I remember stage-managing the performance she did at Naropa. I also met Lanny Harrison who was an original member of Meredith’s company. Lanny and I were performing with Barbara. And through that, Meredith invited me to be in her company. Lanny and I would go on to tour and perform together from 1987 on.

Was Meredith Monk’s company improvisational?

Not at all. We improvised a lot in developing characters and pieces, but on the contrary, Meredith’s work was set to the nth degree—it was very precise. I can still remember the timing of entrances I made in performances of ‘Quarry’150 times over a period of the first two years, and then ten years later for a revival.

You were also working with Ping Chong.

Ping was in Meredith’s company. When I wasn’t working so much with Meredith anymore, Ping asked me to be in one piece, then a second piece with him.

Were you studying while you were working as a dancer?

I went back and studied techniques as best I could: ballet, Erick Hawkins, anatomical release. I knew I was catching up. I was also taking voice lessons. Later on, I was studying with a well-known drama teacher, Ada Brown Mather. She came out of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, and she came to New York for half the year. I did scene study with her for four or five years, really not my cup of tea, but I loved what I was doing. She was very interested in meditation. We had a real friendship, which was sweet. I hung in with her for all that time, even though memorizing lines for scenes didn’t feel like a way forward.

What do you think you learned from working with Meredith Monk?

The longer I live, the more respect I have for what I learned from Meredith. She could be really tough, and I pushed back. What I learned from Meredith was precision, timing, design, the ingredients of experimental theatricality that had nothing to do with scenes and lines. There was almost no text in the work that Meredith did. Vocal sound, but very little text. I never said a word in any of her pieces. Very few people said more than a line here or there. What I brought to Meredith, from working with Barbara and from my own background, was presence, and the work with Meredith enhanced that. I think all the people in the company knew how to radiate presence in performance.

Improvisational performance directed by Steve Clorfeine, Zurich, Switzerland, 2017

In the late seventies, you started Shambhala training and by the mid-to-late eighties you were an instructor. Did you stop performing?

Improvisational performance directed by Steve Clorfeine, Zurich, Switzerland, 2017

In the late seventies, you started Shambhala training and by the mid-to-late eighties you were an instructor. Did you stop performing?

I didn’t really stop. The one time I stopped was when I went to a three-month Buddhist seminary in Pennsylvania. That was a difficult break because I was on a roll. I was cast in Jean-Claude van Itallie’s production of The Tibetan Book of the Dead at La Mama. It conflicted with the seminary, and I went to the seminary.

Appearing in that production might have been a good career move. Do you know why you made that choice?

The career move that it would have been was in the back of my mind, but it never came to the front of my mind. Something in me has always pushed back from ambition of that kind. I played my part. I got grants. I did work. I got reviews. But I don’t have that personality, and I knew that all along.

What did you do at the seminary?

It was an enormous amount of sitting meditation practice, but it was also studying Buddhist texts, listening to talks, being part of a seminary environment, but very social as well.

Were you looking toward leading meditation groups?

I didn’t imagine giving up my performing career or my teaching career. The ground for those dual tracks – teaching and performing - were laid in a parallel way from the beginning, from my Balkan dance days.

You produced a performance piece titled Blue Serge Suite, which was semi-autobiographical and included film.

The first iteration of Blue Serge Suite was in 1979 at St. Mark’s Danspace. Then in 1981 I revised it which included my first film and performed the piece for two weeks at the Warren Street Performance Loft. Making that film came from the influence of Meredith. I had two friends who were in film; one was a film editor, and the other was a cameraman. It was February and we went out to film at the ocean at Brighton Beach in Brooklyn. The section we were filming was a movement piece. It was windy, and the cameraman filmed with sand blowing on the camera, and it was beautiful. I still love that film. From then on, many pieces I would make included film.

My interest in film in live performance is to create another voice, one that is not dependent on my physical presence. It gives the audience a chance to enter another space, to go on a visual journey that offers another landscape and invites another kind of imagining.

Steve Clorfeine in one of the films from Nomad Project #4, 2017

I’ve gotten the impression that your performance workshops are mostly improvisational.

Steve Clorfeine in one of the films from Nomad Project #4, 2017

I’ve gotten the impression that your performance workshops are mostly improvisational.

What I’ve been teaching all along is improvisation. In Europe, it’s called physical theatre, movement theatre. For myself, I’ve only done small pieces that have improvisation in them. Any larger piece is structured.

You worked in Kolkata and Kathmandu in the 2000s as a cultural envoy.

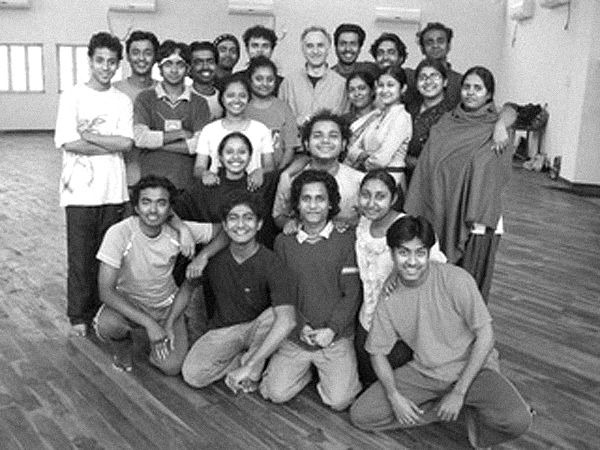

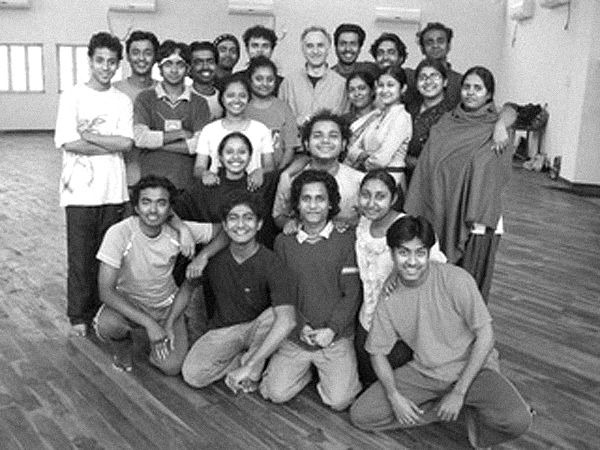

Those were wonderful commissions, well-paid. In Kolkata, it was a six or seven week project, and I was working with undergraduate and graduate students in the theatre department at the major university in East India. It’s called Rabindra Bharati University. The origin of it is Tagore and his family, on whose properties the university was founded. I had to figure out what kind of piece I would be making. I’d worked a lot with personal storytelling. I knew I wanted the piece to involve that. I also knew it was risky because Indian people don’t talk about themselves the way we do. I had a hope that a younger generation of students in a theatre program would be game, and eventually they were.

JHUKI, conceived and directed by Steve Clorfeine;

JHUKI, conceived and directed by Steve Clorfeine;

Kolkata, India, on Rabindranath Tagore’s former family estate, 2008

The first thing I asked them to do was to tell a story about something that happened in their childhood that was transformative. I would get stories about stealing mangoes from the neighbor’s yard and bringing a cat home, things like that. I was able to say that’s not what I mean, but I couldn’t describe what I meant. There was a language issue. Then in one rehearsal this young man, Anirban, who later was invited into the Indian National Theatre, told a story that was spontaneously multilayered and full of understated conflict. And I said, that’s what I’m looking for. The next day another young man came up to me after class and said, Can I tell a dream? I said, please try it. He told a dream that was also multilayered in that way. And then people started to come forward a little bit more. The women were reticent. One woman who was in a theatre company since she was a child, really encouraged the women to come forward. There was a woman who was a kind of outsider, and she told a story that had the implications of being an outsider. Another woman told a story about coming home from school and inadvertently walking into the back room of her house and seeing her uncle hanging from a rope. These are things that are not spoken about in Indian culture. Those stories were told, and they performed them.

Anirban performing his story in JHUKI, 2008

Don’t they have a different performance practice in India?

Anirban performing his story in JHUKI, 2008

Don’t they have a different performance practice in India?

I had four weeks to train them in physical improvisation. They were like nobody I ever worked with. They were so facile in movement. On my website there are videotapes of the two young men I mentioned and others in the performance.

Jayanta Chatterjee solo in JHUKI, 2008

In 2015, you curated a show at Westbeth called Correspondence, and you mounted it later at the gallery at SUNY-Ulster. Is this another track you’re pursuing?

Jayanta Chatterjee solo in JHUKI, 2008

In 2015, you curated a show at Westbeth called Correspondence, and you mounted it later at the gallery at SUNY-Ulster. Is this another track you’re pursuing?

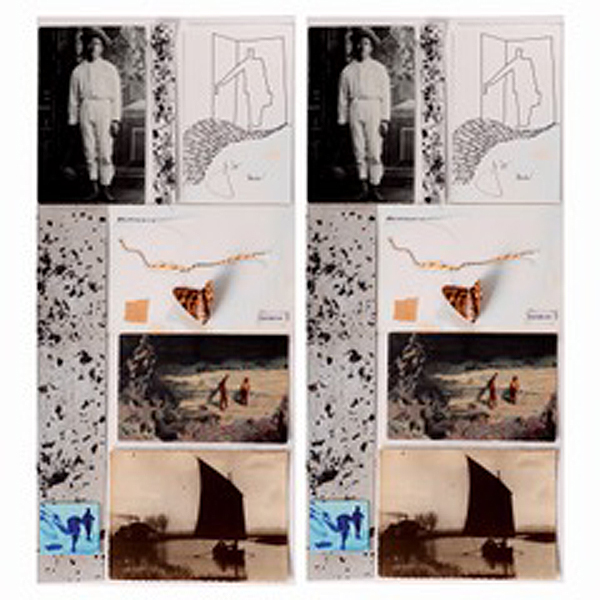

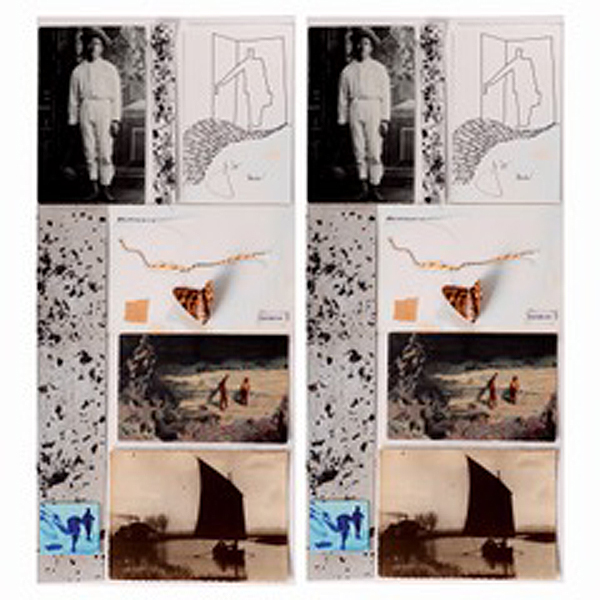

I’ve been doing collage for many years on and off. I came back to it about six years ago. I also saved pretty much every letter that had ever been written to me. Blue Serge Suite has a section with a box of letters in it.

I was really wanting to get rid of these letters. Especially the love letters. That was an emotional decision. I had to stop knowing they were there for me to mull over. I started playing around with things, and then I started collaborating with Christine Alicino, who’s both a commercial and art photographer. I would set up these shots of different stacks of letters and postcards, and she’d shoot them. Then I had the idea to invite friends of mine who are artists to come over, and I’d dump out these letters and postcards and say, pick whatever you want and make something with them. And then it expanded. I had a fellowship at the Vermont Studio Center in 2014 for this project. Some of the young artists at that residency were so interested in the piece that I asked about eight of them to participate. I got the Westbeth Gallery and had friends help mount the show.

Take One/Take Two by Steve Clorfeine in Correspondence show, Westbeth, 2015

Correspondence is a theme in your some of your other work. You teach writing through the idea of correspondence. And you have a section in one of your poetry books that is your response to postcards.

Take One/Take Two by Steve Clorfeine in Correspondence show, Westbeth, 2015

Correspondence is a theme in your some of your other work. You teach writing through the idea of correspondence. And you have a section in one of your poetry books that is your response to postcards.

A good deal of my published work comes out of my journals. I would say that journals are a personal correspondence, basically. I’ve been keeping journals since 1969. At the beginning it was a Gurdjieff task. So for the first five years, my journaling was under that rubric. When I left the Gurdjieff work and started to be at Naropa every summer, the journals became much freer—and they had cutouts and collages in them. It’s been a constant practice for fifty years.

Left to right: Steve Clorfeine, 2002; SC and Tone Blevins in Art on the Beach, lower Manhattan, 1984; SC teaching in Singapore, 2003; SC performing Samuel Beckett’s Act Without Words, New York Shambhala Center, 1999; SC improvisation performance in Cologne, Germany, 2001

Left to right: Steve Clorfeine, 2002; SC and Tone Blevins in Art on the Beach, lower Manhattan, 1984; SC teaching in Singapore, 2003; SC performing Samuel Beckett’s Act Without Words, New York Shambhala Center, 1999; SC improvisation performance in Cologne, Germany, 2001

INTERVIEW WITH STEVE CLORFEINE BY DIANA WALDROP/CODHILL PRESS

August 20, 2015

Interview with Steve Clorfeine on the publication of ‘Together/Apart and other poems’

Diana: What went into the inspiration behind this book? Why does it exist?

Steve: I’m always writing and even though there are spells when I’m not writing, I’m keeping a journal. I tend to go through what I’ve written and revise, rewrite, and when I see a kind of pattern forming, then I think, well, maybe this could move towards a book. So this is the fourth poetry book – three of them with Codhill. I had the title ‘Together/Apart‘ for a long time. That’s how it works for me. In fact, I have the next two titles – I’ve had them for a few years. There was a time when I was really working pretty steadily on all three of these books, and this one got completed, or took its shape, about two years before it was actually published. And then there were delays in the publishing. It was because of the delays that I kept working on the pieces.

The middle section of the book is called “Postcards” and that’s been a collection of poems that has been around in rough and finished forms for maybe 15 years. A few appear in Field Road Sky which was published in 2007. One or two appear in the 2010 book, While I Was Dancing, though they’re not in a form that you would recognize as postcards. But the postcard section in this collection is a conscious attempt to group them together.

About the postcard series – I use postcards as a writing exercise with high school students, and in private writing classes.

In the exercise I spread out a pile of postcards, and ask people to pick one and respond to it in any way they want: investigate everything about the postcard – the image/photo that’s on it, the way it’s addressed, stamped and postmarked, the commercial description of what the picture is, and the contents of the writer. I suggest that – as a way in – one could imagine oneself as an investigative reporter or the nephew or mother of the person who wrote the postcard, or a journalist writing about an event that is the postcard, or just working off the imagery of the front material – the image or photograph. I know most all the people who wrote the postcards I’m offering and the ‘responders’ don’t know them at all so it’s always interesting for me to see what they write. High school students do some amazing things with the exercise. They really go off on tangents that are less censored.

Diana: Is it mostly poetry that the students create?

Steve: Yes. I ask people to write in a prose-poetic form – to write in fragments or lists – to try not to use small words to link thoughts together. Don’t be logical. Let yourself leap from thought to thought; image to image, phrase to phrase. A through line may emerge or a beginning or ending. Occasionally, the postcard itself tells you the beginning or end – there might be something about the salutation at end of the postcard, or the last line of the text.

Here’s a line that ends one of the postcard pieces in the book: “I’ve thought of you many times over the years, wanting to be in touch.” Before that I’ve quoted this person twice, directly from the postcard, so in a way, it’s like a beginning, middle and end. The first quoted line is: “‘I’d love to see or speak with you.” Then towards the end, “‘Life has been a bit too full but with all lucky things,” and then the end is “‘I’ve thought of you many times over the years, wanting to be in touch.’”

Sometimes the body of the message gives me the shape and then in between I play around with the other elements of the postcard. For example, this same postcard poem has a long section about the stamp: “Mary Cassatt (or the subject of her garden portrait) flanked by tall blooming bushes, the foreground and background of the painting set apart by the woman’s white dress, her body fitted to a round wicker chair, arms raised, both hands holding a magazine.” And my comment – “All this on a stamp, six swirling cancellation marks that don’t obscure the stamp’s summer calm.” Then the interjection – “I’d love to see or speak with you,” and then I move to the photograph on the front and from there I comment – “The profile of a thoughtful seated man, forearms resting on a sturdy wooden chair.” I’ve made a parallel to the woman sitting in the chair on the stamp and now the man on the front photograph also sitting in a chair. The parallel interests me and I speculate – “Could he live in the house next to the garden where Mary or her subject sits in the postage stamp image on the reverse side? Having caught a glimpse of a figure in a white dress, might he imagine her snug in a wicker chair in the garden next to his?” All keeping in mind the words of longing of the writer of the postcard.

There’s so much to play with and move around with in the information that’s on a postcard. This is coming from a genre that you might call “Found Text.” It was promoted by a lot of writers, particularly poets, in my early experience teaching and studying at Naropa University. In the early years of the Summer Institute, we each taught one course, and then we could take anybody else’s courses. I did a lot of studying with writers – Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, California poets Joanne Kyger, Diane di Prima – and went to dozens and dozens of readings. That was a real influence on me in terms of my own poetics. When I started teaching writing in schools, I started looking at the fine lineage of writers who developed ways to teach writing in schools – Ken Koch, Jack Collom among others.

Diana: Do you have certain techniques that you always teach or do you change with each class and depending on the students? Do you find one technique that works really well to help people to access that part behind the thinking mind?

Steve: I like to work with free writing to live piano (my wife plays classical pieces and improvises) as a beginning in private workshops in my house. I might offer a prompt – a specific word, phrase, or title. I encourage listening, looking, direct observation of the environment; looking and listening into one’s mind-body of the moment.

Diana: Interesting, so you listen and you write what you think it’s saying? Or…?

Steve: Not so much that—you just write. You don’t try to think about what it’s saying; you just follow the impulse that’s set up in you through listening. I usually ask people to listen for a minute before they start writing and just notice where they are and what they’re bringing to the situation. We work on slowing down and paying attention to details: feelings, what your state of mind feels like. Sometimes I base a writing exercise on asking people to write down everything they can remember about the last 24 hours. In list or fragment form. Then I give a prompt – a phrase or title – and they’ve got this head start – having looked at the situation of the past 24 hours. It’s like opening a window and looking out/looking in. So you’ve got a landscape there as the ground.

Diana: Do you have an example of the types of phrases you would use? Do you just think of them on the spot?

Steve: No, I usually plan them. Sometimes I take them from someone else’s writing. If I read a paragraph or two from someone’s writing, I might use four words or the beginning of a phrase from that. Sometimes I’ll create the phrase myself.

I teach in the Cooperstown high school every year. Two years ago I noticed that I was getting tired of what I was doing. I didn’t force myself to change anything, but I started listening to a 4-CD set of a hundred poets and writers from 1898 to 1990 reading their own work. It Includes the earliest (or only) recordings of Walt Whitman and Gertrude Stein. The recordings aren’t fully audible, but you get a sense. The contemporary writers and poets are varied and really interesting and there were pieces that I honed in on and listened to three, four, five times in order to select what I wanted to work with. That was the development of another way of working. I asked the students to just listen and get the feeling of how the writers were working with rhythm, sound, imagery, with their delivery.

I speak about writing from influence. I pared the recordings down to three or four pieces, and played each piece twice – first for listening and after the second time I asked them to write in that cadence, under that influence—just write under that influence. Although these are advanced writing classes and it’s 8:25 in the morning in high school and they have whatever inhibitions they have, I’m impressed by their willingness to go with it – the rhythms of early Le Roi Jones, for example – really turn them on.

I teach a workshop in my home in Kingston once a month and each time there are five to eight people. When I’m preparing for that, I go through all the materials I’ve collected, and I think about what’s drawing my attention. Then I’ll go back to shelves of poetry books—I’ll go through a few of them and choose some pieces that resonate at the moment, and I’ll start the class like that. Often I’ll read an excerpt from one or two books that I’m currently reading to point out different elements of style or content. So it’s a writing workshop but it’s also a conversation workshop. We share inspirations of other people’s work.

Going back to the book, the postcard poems form the middle section. The last section is called “Place.” I’ve often used the word place as a location for a series of poems. Field Road Sky was mostly lyrical and rural-oriented. Until five years ago I lived pretty deep in the countryside around here. A lot of my writing was drawn from being in a rural place and having a way of seeing and feeling the environment from day to day. An event like an interaction with another person or an animal might be significant because it was the only thing that happened in a day.

Many of those poems began as journal notes that were later shaped and sometimes collaged. I might go through a journal and copy out 50 phrases or paragraphs from a period of six months to a year, cut them up and see how that might fit together into a section or a whole piece. For example, there is a narrative developed around the path across the road from where I lived. I walked there often, so there were seasonal impressions of that path which produced the structure for several poems.

In ‘Together/Apart’ – in the final section – “Place” – the places are all imagined. One is a dream. A couple of them came from a moving and writing duet I do with a partner. Those are images evoked by moving with eyes closed, and combined with free writing, like this one from “The Quarry”: “Over smooth rocks, over watery crevices on their bellies, the women slide like creatures who go silent when approached. When alone they splash wildly, propel themselves off the rock face into air and fly or fall downward, catch the waterfall climb back up triumphant and fly down again.”

Diana: There are three sections of the book – you’ve spoken about the middle section – ‘Postcards’ and the last one, ‘Place.’ What’s the first one?

Steve: The first one is called “Together/Apart.” Much of that is about relationship. The first seven are relationship poems. They investigate the dynamics between two people – some of it drawn from my own experience, my own relationship, and some of it I’m just playing, extrapolating. I’m certainly taking liberties.

Diana: How would you say these three parts connect? Or what is the thread underlying the poems?

Steve: I don’t know that there is a thread. My questions are: “Who I am in my writing at this point; what do I want to put out there?” Some pieces have been waiting on the sidelines – waiting to be fitted in. I’m pleased with the collection ‘Together/Apart’. I hear it as my voice now, even though it’s not “now” anymore. The newest poems just slipped in about six months ago; the others are anywhere from the past two to seven years. The last piece in the book is sourced from a guy who sublet my apartment many years ago and wrote me a note in broken English that was like a mirror of my life. Later I transformed it into a performance piece where a character comes back from a two -month theater tour, re-enters his apartment and sees this note on the table. The performance begins with me reading this note. Then it transformed again in the next iteration of that performance piece. In the third iteration 15 years later, I brought it up to date by shifting it from the original apartment note to a mixture of the original note and a note that someone who sublet my house in the countryside had written to me. I also imagined a note I would have written about staying in my house. It’s a pretty straight narrative piece, more so than most of the others.

Diana: What do you mean?

Steve: Many of my poems make leaps and challenge the reader/listener to resist trying to figure it out logically but rather to catch the arc and just ride it, tune in to the feeling of it, to the way I’m speaking it or the way my voice has written it down. My writing is coming more from my voice than from a literary style. I’m speaking the words that I’m writing. Many of the poems work as spoken pieces. They have a spoken sense that may come through differently than on the page. On the other hand, someone could read it on the page at different times and get something other than what they got hearing it aloud only one time. I guess it goes both ways.

Diana: As far as the form of each poem, is it just kind of random or did you use a specific form in writing these poems?

Steve: The relationship poems are all “he” and “she.” That was a choice I made. Once in a while, an “I” will slip in, like in this one “I draw a picture with a story—it’s you and somehow more.” But generally it’s he and she or you.

Some of the poems in ‘Together/Apart’ have numbered stanzas. The longest is five stanzas. That’s the way I’m moving from one thought to another, or shifting from one time frame to another.

There’s a long poem called “Begin Again, Spring,” and it’s based on notes I made when I sublet an apartment five years ago on the upper west side. It was Spring and I would take a walk every day in Riverside Park or Central Park, so this poem is a collection of notes from those walks and I mixed them together as if it was one park, one day.

Often, repetition is part of the structure – like referring to a dream and referring to the moon, in the poem “Here’s What Happens.” Sometimes it’s a dream shaped into a story—like the piece “S. Klein on the Square.” It’s a story. It moves that way. There’s a flashback in it, but basically it moves right along—in what you could imagine to be 5 or 10 minutes of time passing.

Diana: How do you know when a poem is finished or ready? Or do you ever know?

Steve: Maybe I’m a little lazy about that because I tend to know that it’s finished when the last line works. After that there will be more work on it, but sometimes that’s the way I know. I might be looking for the ending and it may come from the body of the piece itself, as if it was heading that way from the beginning. In one of the postcard poems, I’m in residence in a theater school in Amsterdam and I’m writing to a friend. I’m using her actual postcard and my imagined response to her. At the end I write, “Imagine us meeting in the Gemeente Museum wearing clogs speaking like Nederlanders.” I’m mixing two worlds in different time frames. The postcards seem to find their own endings. In a short story – that’s where I often struggle with an ending.

Diana: Do you write more poetry rather than short stories?

Steve: I write more poetry or at least I publish more poetry. I’ve published one nonfiction book. Two projects that have been going on for some years; one is a memoir piece, a collection of stories from the time I was 8 or 9. Most of them are childhood stories. And the other book I’m working on is nonfiction – based on my journals and travels in India for the last 20 years.

Diana: is that like the Nepal book?

Steve: The Nepal book was published in 2000 and was based on three long trips to Nepal. This one begins in ’95 and goes until I stop traveling to India and get this book out. It’s a hard one because India is changing so fast. The earlier notes I kept are so different in tenor from current ones.

Diana: As far as reading poetry, what advice would you give, or maybe take for yourself, about how to read poetry? I don’t think there’s one answer to that – does that make sense?

Steve: You mean if you pick up a poetry book, how to read it?

Diana: Yes, because you can read poetry and you’re not really feeling it because you’re trying to intellectualize it. So basically, how do you stop intellectualizing it and actually get into it without getting stuck on the mental level?

Steve: That’s an interesting question. Two things come to mind: one is based on the choice of poetry you want to read at any given moment. Where does that come from? I’ve got four shelves of poetry books. If I’m looking for inspiration for a writing workshop or to read aloud to someone, I often browse through familiar collections to see what I’m drawn to. It could be a phrase or a reference to something that interests me, and so I’ll go back to the beginning of that poem, and I’ll read it through. Then I look at the poems before and after that one. I had an appreciation for a sort of random inquisitiveness. I wasn’t expecting anything. Other times I’ll take a familiar collection and I’ll search out poems in it that I haven’t looked at before.

The second thing I was thinking about in relation to your question is that I sound poems out in my head – I’m actually reading them aloud and listening to that voice in my head. That could be helpful to people who tend to intellectualize – read it aloud or just speak it out in your head so that you’re not dwelling on the words but you’re letting the words come into you. Feel what that stirs up in you. You can always intellectualize later, but it’s probably not the best way to begin.

CORRESPONDENCE-

CORRESPONDENCE- a curatorial installation by Steve Clorfeine presenting the work of 40 artists, each invited to create works inspired by letters and postcards writen to Mr. Clorfeine over a period of 50 years.

More about the exhibit

A note from the curator

When I first conceived the project, I was sorting through 7 shoeboxes of letters and postcards that I’d saved since 1962. Some of the correspondence had continued for 30-45 years and stood in stacks 4-6” high. Starting in college, a year abroad in Paris, graduate school, another year abroad in Eastern Europe, summers teaching at Naropa University in Boulder, Co., on tour in Europe performing and teaching, studying and teaching in Nepal and India – letters and postcards kept me connected as I shifted place and persona.

What to do with all of this? I set aside long-standing correspondences as well as family and intimate letters. The remainder went into a shopping bag to be burned. That never happened. A few years went by until the idea came that the material could be transformed. I invited a few artist friends to choose from the collection and create an artwork. Through our mutual enthusiasm the idea grew and I invited more friends – visual and performing artists – near and far. The final group materialized during a residency at Vermont Studio Center this past Fall. At the same time I began to burn the love letters and most of the intimate correspondence and created a series of ash drawings and collages.

In this project, the correspondence is re-ignited as found text and revealed as an installation site of friendship and discourse. It moves into a three dimensional present through a process of fabrication and interpretation.

There is another aspect of correspondence which plays in this exhibition: what corresponds to what and how. In the present moment there is ultimate correspondence – things are as they are. We can draw inspiration from the way things are as we perceive their relationships before we judge or interpret.

Correspondence: relationship across time and space. Thoughts and feelings across the page.

When I write to you, I remember you now. Even before I write your name, you are there – in mind. We are in correspondence. We tell the news, we write our stories, and the invisible intimacy of our relationship leaves marks in the visible world.

Hands on: pen/typewriter/paper

Salutation/body/signature/address/stamp/post

Wait/receive/read/feel.

Steve Clorfeine is a performer, writer and teacher with a life-long interest in stories and coincidence.

PART 1: INTERVIEW WITH FLORENCE DERAIL

I grew up in New York City and returned after university and lived there on and off up to this point. I’ll say a bit about my influences. because I think that in the

When I was a kid my parents were interested in performance as a part of culture and they had friends who were professional musicians, photographers, painters. They tried to see as much theatre and dance as possible and particularly world dance, ethnic dance. So as children, living in New York City, we went to all the great theatres to see plays and dance concerts. At that time Broadway was rich with musical theatre as well as dramatic theatre. It was a great age for theatre and for presentations of major ethnic dance troupes from around the world.

By the time I was in high school, I was able to go to the theatre by myself and with friends a few times a week. Students could see everything that was on Broadway and Off-Broadway with special $1. tickets on the slow nights, Tuesday - Thursday. Of course I took theatre classes and I did some acting in school but I never really thought about it as something that I would do in my life.

Another thing that was very strong for me was dancing. My parents were connected to folk dance circuits. There were regular groups in our neighborhood which met one or two times a week. My parents would often go away on weekends to folk dance festivals in the countryside. It was a popular thing to do at that time. So through them I became involved in folk dancing - I had no choice! I was too young to stay by myself at home and we didn’t have money for someone to take me somewhere else.

When I went to university I left that behind. I got very involved in academic studies and I didn’t really come back to theatre and dance until post-graduate studies in the Eastern European Institute at Columbia University. I studied Balkan dance, music and culture which saved me from the dryness of academics at Columbia. At university I went to Paris to study for a year and while at Columbia I had fellowships to study in Prague and Yugoslavia for a year. I had a strong connection to Europe from an early age.

Where it started to come together was when I was teaching at the State University in New York. I was teaching Balkan dance and Balkan culture but I was also creating a program of world music and dance. That had a great effect on me - opening me up to African dance, Latin dance, Indian dance, Native American dance and vernacular tap dance and jazz.

When I left the university job I was 27. I knew that academics was not the way I was going to fulfill myself but I still didn’t know what the way was going to be. With that kind of open question and almost by accident, I went to the first summer program at the Naropa Institute in Boulder Colorado.

I had been on a spiritual path for five years already through the Gurdjieff work - I was part of the Gurdjieff Foundation in New York. When I went to Boulder I met Trungpa Rinpoché and other people who would have a great influence in my life, particularly Allen Ginsberg and Barbara Dilley. Allen in terms of writing and Barbara in dancing (improvising) and Trungpa Rinpoché: that was a triangle of influences! Looking back I see those influences as the beginning of a direct line of both transmission and inspiration that have stayed with me.

Those original connections haven’t wavered. I feel lucky to have been open to that contact at that moment in my life. The connection that really pushed me forward in terms of livelihood and career was the connection with Barbara because she invited me to be part of her performances later that year, 1974. So I came back to New York City and started performing with Barbara. Then I continued to go back to Naropa every summer. The first time I was an assistant for Barbara and then I started teaching on my own, both Balkan folk dance and also improvisation.

The second summer of Naropa, 1975, I met Meredith Monk and we became good friends through two persons who were also very important in my life - Lanny Harrison, who was a member of Meredith’s company and Collin Walcott who was a musician in a jazz band called Oregon. We all really connected and I was invited to be part of Meredith ‘s theatre company.

That was the root of my new theatre career, suddenly being in Meredith's company, being paid a salary and making ensemble theatre pieces that would travel to Europe, play for a month at La Mama Theater in NYC, and go on to play a hundred performances in Europe and the States. I studied and absorbed the way Meredith did things and I was also catching up on training in dance. A lot of it was new dance and improvisation but I also studied techniques like Eric Hawkins and some ballet. New forms were popping up all over: Ideokinesis with Irene Dowd, Nancy Topf’s anatomical release, Steve Paxton and contact improvisation. I was studyng with these people as they were first developing these forms of improvisation.

It was an incredibly rich time in NYC from 1974 to 1983. After that there was a kind of cultural shift. Dance and theatre companies started to get big grants and subsidies and were competing with each other; moving onto different levels actually so the culture of downtown NYC loft performances where everyone mingled and saw each others' work on a regular basis and everybody seemed to know everybody, that started to diminish.

By the early 1980’s my studies in Buddhism and Shambhala teachings were getting very demanding. I was going to dathun (one month retreat) and completing the first cycle of Shambhala training and then going to the three month vajrayana seminary, Kalapa assembly, and starting to be a meditation instructor and to direct programs. This was the middle of 1980’s where a deeper and more consistent study in Shambhala Buddhist teachings was mixing with performing and with theatre teaching.

At the same time, I began to teach in artisit-in-residence programs in public schools. It was good livelihood and the work felt close to contemplative practice. I taught storytelling and improvisation residencies in high schools and with smaller children, as well as creating training workshops for teachers. This took a lot of my focus during that time and it's something I continue to do; particularly the teacher training. I've constructed a curriculum for training theatre teachers which is based on improvisation with movement and images, text and props. It’s a way of making theatre based on what’s on hand. (slides from Kurten) The text doesn’t come from scripts and the concepts don’t come from outside; we make it together.

I call it Theatre on the Spot and that’s basically what i love to do in training - working as an ensemble and creating the ground for making a performance through improvisation.

Question: What is the influence of Buddhism in your work?

From the very beginning of The Naropa summer programs, Trungpa Rinpoché told us as the summer faculty that he really had confidence in us, that we could transmit what we were studying and practicing in terms of meditation practice; that we could transmit that through our teaching in arts disciplines- and particularly in the work with visual dharma or Dharma Art which had an influence on all of us, actually quite a big influence.

Dharma Art works at the very heart of human experience: sense perceptions and particularly where those intersect with how the mind works. It’s looking into how we see things, how we hear things, how we feel things and what we do with that information. Though we often distort sensory information, we also have the potential to receive it and transform it into pure expression, the expression of direct experience, direct perception. From the very beginning that was a very strong and rich thread in the process. The way of looking at and noticing what you are doing, not being afraid to not know what you are doing and to watch yourself finding a way.

We have a concept that the teacher has their preparation, has their notes and exercises and you just do them, and maybe you think about it afterwards and review or change your presentation a little bit. But here there is a challenge to witness yourself as you are doing these things and relate from moment to moment to what is needed in the room with the people who are there. So you are challenged to shift the way you do things, you can let go and have a gap and not know what you are going to do and wait until an idea arises or just have a period of silence or reflection. You are not afraid to be exposed that way; your mind works with the situation and engages people in the way of that process. This attitude can grow so that it becomes an intuitive way that you are working and relating. You are working with knowing and with not knowing and you are wiling to step through the doubt that arises in that process.

I think we begin to see that this is innate in the Mudra Theatre space awareness exercises, the essence being that you are present, receptive from moment from moment. You are working with knowing and not knowing, being present, drifting away, coming back to being receptive and being again distracted and coming back. These are not opposites and they don’t conflict with each other, it’s actually more like a dance and the wholeness of any moment is containing both of those possibilites: being present and being distracted, being present and seing things clearly, experiencing with a relative clarity and then losing it, drifting off, having a thought about something else. We expand what we can accept. There is a wonderful phrase from Suzuki Roshi, the great Zen teacher: “Big mind, little mind;” big mind is more the mind that holds these shifts with a sense of presence even as things are changing from moment to moment; it’s not trying to grab onto something and work with the particular distraction that’s coming up so much or work with the beauty that’s coming up so much, but holding that in the centre of what’s going on while the larger circle is being present to all of it. Like the poet Lew Welch writes, “I saw myself a ring of bone in the clear stream of all of it/ and vowed always to be open to it/that all of it might flow through.” This becomes a powerful experience in improvisation.

Fundamentally what a lot of us have found in working with improvisation is that there are parallels between awareness practice and improvisation practice, and the parallels are so consistent that one can after years of working like this begin to articulate them and set up situations in which people can have that parallel experience and can inform themselves through that experience. You don’t need to explain what is going to happen but you set up the situation and people have the experience and become their own teachers. Then we are training together: ensemble.

Question: You create conditions?

Yes. I’m attracted by ensemble performance because the basis of it is acknowledging that we are held by collective conditions when we are working together and from those conditions we can create together. Each of us has their individual way of moving through those conditions and the more receptive we are to each others’ particular way of moving through, the more the ensemble can grow, the more accepting and the more demanding it can be. Each person is challenged to open up further, to not be afraid to show themselves more openly. That sounds like the message of daring, the message of the warrior in the world.

Question: This was the foundation of your work with Barbara Dilley and Meredith Monk?

Right from the beginning my experience with Barbara was particularly strong in that way. With Meredith it was more learning about creating performance in terms of imagery: film sound/music, and using movement images. With Barbara it was learning “pure” improvisation - being out there in that field of not knowing. Barbara represented that so fully. The group that had a strong influence on me was an ensemble improvisation company called the Grand Union. It didn’t last for very long, maybe 3-4 years. It was a group of choreographers. Barbara, Trisha Brown, David Gordon, Douglas Dunn, Nancy Lewis and Steve Paxton. Yvonne Rainer was the initiator. They would come to a performance space with no script at all. Maybe they’d worked together informally, maybe they had been in casual contact but they came to the performance space and improvised performance, creating situations, imagery and stories using props, language, movement, music. It was amazing to watch that unfold; it was like swimming in water that came to feel like the room itself and the audience was in the water with the performers. Not cozy or comfortable so much but essential continuous unfolding. The Grand Union group was a great influence on me. There were connections to that kind of work, that kind of spirit that I found in other places – in Peter Brook’s work, in Grotowski’s work in the Polish Theatre Lab and also in Taddeus Kantor’s work that I had contact with over the years.

Question: When I see this kind of work I feel a great simplicity, a sort of relaxation, availability…they are so alive…

When I watch a group like that I sense they’ve been together in a profound and intimate way to be able to give this kind of performance. In terms of Grotowski’s and Cantor’s theater, it’s coming from a lived experience, a collective, emotional lived experience. There has been suffering, there‘s been conflict, joy, revelation, there’s been all of that before we see them and when they come to us on stage, those emotions and that emotional history are moving through them. We are drawn in by that so rather than just absorbing what’s given, something of our own emotional history becomes engaged with them, we become part of what they are doing, of what’s being made visible. That’s the essence of theatre, the essence of what Peter Brook and others call “making the invisible visible” – eliminating the separation between audience and performance by being relaxed and confident enough to invite the audience deeply into the space.

Question: We cannot reach this level without working a certain amount of time together…the notion of troupe, company is essential for me…it seems so difficult to work like this in the actual world…we’re losing a certain sense of collective in society these days, it makes me sad.

Yes you know Andre Serban talks about that. He wrote a wonderful essay where he says that he can’t believe that people are asked to put up a play in six weeks or even eight weeks…he says for him, it’s one or two years. There was a point where he actually stopped doing theatre altogether because he didn’t see it as a process that was framed properly. All the conditions of finances: renting space, a theatre, publicity, schedules, all that was eating up open energy to explore.

I like what you are saying – ideally we are looking for a situation that is ongoing so that we can explore together the history that we are creating by being together from day to day; that each day we come back and we have an agreement that something is offered to the mixture of the collective and yet we don’t hold on to that, we renew and regenerate it in an ongoing way. I think there’s good discipline that happens naturally. People can fall apart and pick themselves up again and do it for the benefit of the group; you might let go a bit more your attachment to your mood, recognizing that as “small mind.”

In fact, it’s important for us to get through the mood, absorb the mood. Otherwise, it can be a distraction from our openness to ensemble work. As we work together and deepen our experience, we can encourage each other to relax around our personal stuff and let it be part of the information that we are collecting and creating together.

Fundamentally people know how to open up, how to be receptive and come back to that situation, that space where we have direct access to ourselves, to our own spot, our own hearts, our sense of being ourselves.

It’s not this subjective partner controlling our experience with conditions and preferences and demands and so forth; it’s a more open partnership with ourselves. We are training ourselves to relax our reference point and part of that is relaxing around our egos (laughs!). There’s nothing wrong with our egos…but when we hold them so tightly that nothng gets in, that’s a problem. In theater and improvisation practice we can find moments together where the ensemble recognizes relaxing around egos and the space becomes a partner, direct experience becomes a partner in a direct way; it’s not so random anymore. You are not waiting for your muse to sing the song or dance the dance!

Question: It’s also a possibility to free up joy, cheerfulness, a sense of energy.

Yes. I think cheerfulness is related to receptivity and the sense that things are just doing what they do and being what they are; in the same way I am doing what I do, I am being who I am despite the problems, conflicts, the issues and the obstacles…

We tend to be so serious, maybe artists especially, we struggle with being such serious people. Noticing this seriousness, and the defensiveness that arises around it, we can relax and then a little sense of humour bubbles up.

Thank you Steve.

MINDFULNESS AND IMPROVISATION: A CONVERSATION WITH STEVE CLORFEINE BY LYNN HARTLEY

Over the last ten years, Steve has been on the Authentic Leadership in Action (ALIA) arts faculty, which leads creative process sessions. At ALIA, creative process helps leaders become more fully attuned, moment-to-moment, to what is happening.

“When people come to creative process, they have been spending a lot of time sitting in a chair, absorbing new theory, being in conversation. And then suddenly there comes a moment when they can let all that go. They can move into another part of themselves. It also balances mental and verbal engagement.”

Improvisation also invites bravery and a willingness to engage in what Steve describes as “not knowing and using everything you have to go forward.” He elaborates:

“It is always a challenge to bring more of ourselves into the present. Through mindfulness we come to notice our hesitation, our resistance. It takes effort to bring that in, to not be afraid of ourselves. By mixing mindfulness and improvisation, we invite a bit more of ourselves, from outside our usual comfort zones or strategies. How much can I include in being present? Can I include not being present? Can I include being afraid? Can I include hesitation and resistance? How much can I include? To me that is the question at the heart of improvisation.”

This type of improvisation is very different than people’s preconceived ideas: “People often speak about improvisation as going wild—doing whatever you want. I’m speaking about something different, about stretching or expanding your attention and absorbing as much as you can, as directly as you can, to inform the choices you make.”

In the creative process sessions, people begin to directly experience what is happening within themselves, in a playful way. “There is tremendous discipline in deep play. When you think of it from a child’s point of view, it’s almost an instinctive discipline. When you watch children play, they are completely absorbed in what they are doing. It is a natural discipline of attention.”

While play may be natural to children, as we get older, we often lose the ability to fully engage in the moment. “We lose our confidence that it’s okay to play. We give in to the demands of being adolescents or adults and wrap our egos into those responsibilities. We don’t give ourselves the opportunity to play. I think this is why when we as ALIA artists improvise together, it’s scary on a certain level. Sometimes we don’t even have a plan even though we spend a lot of time pretending to plan!"

“Scary is another way of saying, it is so deeply poignant that you can hardly get a grip on yourself. The call to openness is the call to compassion—compassion for yourself and compassion for others. As my friend Ruth Zaporah says about improv, “Everything your partner does is perfect.”

Four-Minute Improv Exercise

Stand facing in one direction, wherever you are, and scan the horizon.

Notice what you notice.

Shift your weight, pivot, and turn to face the next direction.

Take the first few seconds to receive the new shape of what is in front of you. Then begin to scan the horizon, from left to right.

Repeat in each of the four directions, for one minute each time.

Notice how you feel.

Steve’s reflection on the four-minute exercise:

“I notice that slowing down this way invites vividness. Slowing down and receiving what’s in front of you and at the periphery – just receiving it, without judgment – this invites openness. I notice my state of mind—sometimes it is difficult to slow down. I might notice the running commentary that I have about everything going on. I want to receive things directly, and yet I have some interference, a kind of editorializing. All these things come up very quickly, and it is all very useful.”

Main Menu

© Steve Clorfeine 2023